Understanding the Context

Crisis and emergency contexts involve sudden and significant disruptions such as natural disasters, family violence, homelessness, pandemics, and trauma. These situations can have lasting effects on a child’s emotional, social, and cognitive development (Perry, 2006).

Relevance in ECE

Early childhood educators play a crucial role in offering safety, stability, and emotional support. Consistent routines, secure relationships, and trauma-informed care help children feel safe and recover from distress (Bromfield et al., 2022).

Theoretical Lens:

Trauma Theory: Highlights how overwhelming stress can impair brain development and behaviour (Perry, 2006).

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory: Describes how crises impact children through changes in their environment (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Explains how children need safety before they can focus on learning (Maslow, 1943).

Contemporary Reflection

Australia has faced increasing emergencies—from bushfires to COVID-19—highlighting the need for trauma-aware education and support services (AIHW, 2023). The rise in domestic violence and displacement has also affected many families’ access to education and housing (Australian Government, 2020).

Impact on Children and Families

Children affected by crisis may experience:

Anxiety, fear, or aggression

Interrupted routines and poor concentration

Loss of housing, education, or loved ones

Disengaged caregivers under stress

Social Policy and Australian Responses

National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework (Australian Government, 2020)

Safe at Home Programs for family violence

COVID-19 Education Recovery Plans

Mental health support from Beyond Blue, Kids Helpline, and Headspace

Strategies for Practice

Implement Trauma-Informed Practices

Evidence Base: Trauma-informed education helps reduce stress responses and supports brain development (Perry, 2006).

In Practice:

Create calm, predictable routines and safe spaces.

Use soft tones, gentle touch, and visual schedules.

Be patient with children who display withdrawal, aggression, or fear.

Build Strong, Trusting Relationships

Evidence Base: Secure attachments foster emotional resilience and recovery (Bowlby, 1988).

In Practice:

Prioritise warm, responsive interactions.

Offer consistent caregiving and comfort.

Use key educators to maintain familiarity and trust.

Use Play for Emotional Expression and Healing

Evidence Base: Play helps children process trauma and express emotions safely (Landreth, 2012).

In Practice:

Provide materials like puppets, clay, sand, and drawing tools.

Allow children to lead play without pressure.

Observe themes in play to understand emotional needs.

Support and Engage Families

Evidence Base: Family-centred practice strengthens children’s outcomes (Dunst & Espe-Sherwindt, 2016).

In Practice:

Listen to families’ stories with empathy and confidentiality.

Offer flexible meeting times and community referrals (e.g., housing, food relief).

Encourage families to be part of planning their child’s support.

Promote Emotional Literacy and Regulation

Evidence Base: Teaching emotional skills helps children recover from stress and develop resilience (Denham et al., 2012).

In Practice:

Use picture books and visuals to name and explore feelings.

Model and teach self-soothing (e.g., deep breaths, calm corners).

Use group time to discuss safe choices and empathy.

Community and Professional Partnerships

Educator’s Role in Collaboration

Build trust with families to identify needs early.

Refer sensitively using clear, non-judgemental language.

Maintain communication with external partners while respecting family confidentiality.

Document concerns and share only relevant information with consent.

Participate in care planning with professionals to ensure coordinated support.

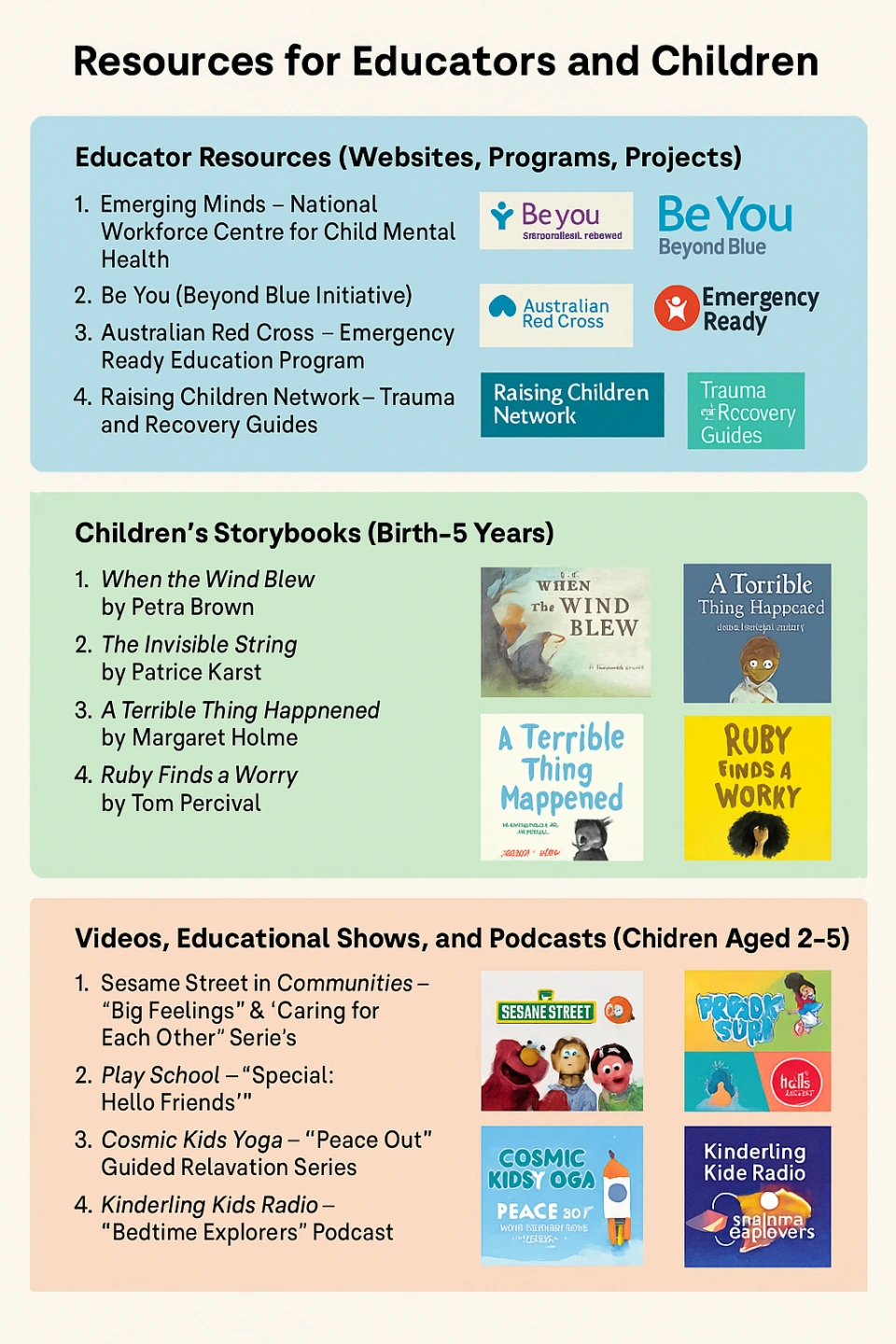

Resources for Educators and Children

Photo

🌟 Educator Resources